Environmental Psychology 5th Edition Bell Pdf Printer

Posted on

Environmental Psychology 5th Edition Bell Pdf Printer Rating: 8,4/10 5380 reviews

Psychology 5th Edition By Hockenbury

- Acham, K. (2003). Zu den Bedingungen der Entstehung von Neuem in der Wissenschaft [Conditions of the emergence of novelty in science]. In W. Berka, E. Brix, & C. Smekal (Eds.), Woher kommt das Neue? Kreativität in Wissenschaft und Kunst (pp. 1–28). Vienna: Böhlau.Google Scholar

- Alligood, M. R. (1991). Testing Roger's theory of accelerating change: The relationship among creativity, actualization, and empathy in persons 18 to 92 years of age. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 13, 84–96.Google Scholar

- Amabile, T. M. (1979). Effects of external evaluation on artistic creativity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37, 221–233.Google Scholar

- Amabile, T. M. (1983a). The social psychology of creativity. New York: Springer.Google Scholar

- Amabile, T. M. (1983b). Social psychology of creativity: A componential conceptualization. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45, 357–377.Google Scholar

- Amabile, T. M. (1988). A model of creativity and innovation in organizations. In B. M. Staw & L. L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior, Vol. 10, (pp. 123–167). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.Google Scholar

- Amabile, T. M. (1995). KEYS: Assessing the climate for creativity. Greensboro, NC: Center for Creative Leadership.Google Scholar

- Amabile, T. M. (1996). Creativity in context: Update to the social psychology of creativity. New York: Westview Press.Google Scholar

- Amabile, T. M. & Conti R. (1999). Changes in the work environment for creativity during downsizing. The Academy of Management Journal, 42, 630–640.Google Scholar

- Amabile, T. M. & Gryskiewicz, N. (1989). The creative environment scales: The work environ ment inventory. Creative Research Journal, 2, 231–254.Google Scholar

- Amabile, T. M., Goldfarb, P., & Brackfield, S. (1990). Social influences on creativity: Evaluation, co-action, and surveillance. Creativity Research Journal, 3, 6–21.Google Scholar

- Amabile, T. M., Conti R., Coon, H., Lazenby, J., & Herron, M. (1996). Assessing the work environment for creativity. The Academy of Management Journal, 39, 1154–1184.Google Scholar

- Ambrose, D. (2006). Large-scale contextual influences on creativity: Evolving academic disci plines and global value systems. Creativity Research Journal, 18, 75–85.Google Scholar

- Andre, T., Schumer, H., & Whitaker, P. (1979). Group discussion and individual creativity. Journal of General Psychology, 100, 111–123.Google Scholar

- Andrews, F. M. & Farris, G. F. (1967). Supervisory practices and innovation in scientific teams. Personnel Psychology, 20, 497–515.Google Scholar

- Anspach, E. (1952). The nemesis of creativity: Observations on our occupation of Germany. Social Research, 19, 403–429.Google Scholar

- Anthony, K. & Watkins, N. (2002). Exploring pathology: Relationships between clinical and envi ronmental psychology. In R. B. Bechtel & A. Churchman (Eds.), Handbook of environmental psychology (pp. 129–145). New York: Wiley.Google Scholar

- Arieti, S. (1976). Creativity: The magic synthesis. New York: Basic Books.Google Scholar

- Banghart, F. D. & Spraker, H. S. (1963). Group influence on creativity in mathematics. The Journal of Experimental Education, 31, 257–263.Google Scholar

- Barker, R. G. (1968). Ecological psychology: Concepts and methods for studying the environment of human behavior. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.Google Scholar

- Barron, F. (1955). The disposition toward originality. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 51, 478–485.Google Scholar

- Barron, F. (1969). Creative person and creative process. New York: Holt, Rinehardt & Winston.Google Scholar

- Barron, F. B. & Harrington, D. M. (1981). Creativity, intelligence, and personality. Annual Review of Psychology, 32, 439–476.Google Scholar

- Bateson, G. (1972). Steps to an ecology of mind. New York: Ballantine Books.Google Scholar

- Bateson, G. & Bateson, M. (1987). Angels fear: Towards an epistemology of the sacred. Toronto: Bantam Books.Google Scholar

- Becker, G. (2000–2001). The association of creativity and psychopathology: Its cultural-historical origins. Creativity Research Journal, 13, 45–53.Google Scholar

- Bell, P. A., Greene, T. C., Fisher, J. D., & Baum, A. (2001). Environmental psychology. 5th edi tion. Forth Worth, TX: Harcourt College Publishers.Google Scholar

- Bergler, E. (1950). The writer and psychoanalysis. Garden City, NY: Doubleday.Google Scholar

- Berkes, F. (1999). Sacred ecology: Traditional ecological knowledge and resource management. Philadelphia, PA: Taylor & Francis.Google Scholar

- Berlin, I. N. (1960). Aspects of creativity and the learning process. American Imago— A Psychoanalytic Journal for the Arts and Sciences, 17, 83–99.Google Scholar

- Biersack, A. (1999). Introduction: From the “new ecology” to the new ecologies. American Anthropologist, New Series, 101, 5–18.Google Scholar

- Bloomberg, M. (1967). An inquiry into the relationship between field independence-dependence and creativity. Journal of Psychology, 67, 127–140.Google Scholar

- Bloomberg, M. (1971). Creativity as related to field independence and mobility. Journal of Genetic Psychology, 118, 3–12.Google Scholar

- Boden, M. (1994). What is creativity? In M. Boden (Ed.), Dimensions of creativity (pp. 75–117). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Google Scholar

- Boden, M. (2004). In a nutshell. In M. Boden (Ed.), The creative mind: Myths and mechanisms (revised and expanded 2nd ed.). London: Routledge (pp. 1–24).Google Scholar

- Bond, C. F., Jr. & Titus, L. J. (1983). Social facilitation: A meta-analysis of 241 studies. Psychological Bulletin, 94, 265–292.Google Scholar

- Bonnes, M. & Secchiaroli, G. (1995). Environmental psychology. London: Sage.Google Scholar

- Briskman, L. (1980). Creative product and creative process in science and the arts. Inquiry: An interdisciplinary journal of philosophy23, 83–106.Google Scholar

- Brown, A. D. & Starkey, K. (2000). Organizational identity and learning: A psychodynamic perspective. The Academy of Management Review, 25, 102–120.Google Scholar

- Brown, V. , Tumeo, M., Larey, T. S., & Paulus, P. B. (1998). Modeling cognitive interactions dur ing group brainstorming. Small Group Research, 29, 495–526.Google Scholar

- Brunswik, E. (1956). Perception and the representative design of psychological experiments. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.Google Scholar

- Brunswik, E. (1957). Scope and aspects of cognitive problems. In J. S. Bruner (Ed.), Contemporary approaches to cognition (pp. 5–31). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.Google Scholar

- Burchard, E. M. L. (1952). The use of projective techniques in the analysis of creativity. Journal of Projective Techniques, 16, 412–427.Google Scholar

- Campbell, J., Dunnette, M. D., Lawler, E. E., & Weick, K. E. (1970). Managerial behavior, per formance, and effectiveness. New York: McGraw-Hill.Google Scholar

- Candolle, A. de (1873). Histoire des sciences et des savants depuis deux siecles [History of sci ence and scholarship over two centuries]. Geneva, Switzerland: Georg.Google Scholar

- Canter, D. (1977). The psychology of places. London: Architectural Press.Google Scholar

- Canter, D. (1985). Putting situations in their place: Foundations for a bridge between social and environmental psychology. In A. Furnham (Ed.), Social behavior in context (pp. 208–239). London: Allyn & Bacon.Google Scholar

- Carlozzi, A., Bull, K. S., Eells, G. T., & Hurlburt, J. D. (1995). Empathy as related to creativity, dogmatism, and expressiveness. Journal of Psychology, 129, 365–373.Google Scholar

- Choi, J. N. (2004). Individual and contextual predictors of creative performance: The mediating role of psychological processes. Creativity Research Journal, 16, 187–199.Google Scholar

- Clapham, M. M. (2000–2001). The effects of affect manipulation and information exposure on divergent thinking. Creativity Research Journal, 13, 335–350.Google Scholar

- Clitheroe, H. C., Stokols, D., & Zmuidzinas, M. (1998). Conceptualizing the context of environ ment and behavior. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 18, 103–112.Google Scholar

- Cooper, R. B. & Jayatilaka, B. (2006). Group creativity: The effects of extrinsic, intrinsic, and obligation motivations. Creativity Research Journal, 18, 153–172.Google Scholar

- Couger, J. D. (1995). Creative problem solving and opportunity finding. Danvers, MA: Boyd & Fraser.Google Scholar

- Cropley, A. (2006). In praise of convergent thinking. Creativity Research Journal, 18, 391–404.Google Scholar

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). The domain of creativity. In M. A. Runco & R. S. Albert (Eds.), Theories of creativity (pp. 190–212). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.Google Scholar

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1988). Society, culture, and person: A systems view of creativity. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), The nature of creativity (pp. 325–339). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.Google Scholar

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1999). Implications of a systems perspective for the study of creativity. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Handbook of creativity (pp. 313–335). New York: Cambridge University Press.Google Scholar

- Cummings, L. L. (1965). Organizational climates for creativity. The Academy of Management Journal, 8, 220–227.Google Scholar

- D'Agostino, F. (1984). Chomsky on creativity. Synthese, 58, 85–117.Google Scholar

- DeBono, E. (1968). New Think. New York: Basic Books.Google Scholar

- Deci, E. L. & Ryan, R. M. (1980). The empirical exploration of intrinsic motivational processes. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 13, pp. 39–80). New York: Academic Press.Google Scholar

- Deci, E. L. & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York: Plenum.Google Scholar

- Denison, D. R. (1996). What is the difference between organizational culture and organizational climate? A native's point of view on a decade of paradigm wars. The Academy of Management Review, 21, 619–654.Google Scholar

- Department of Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) (1998). The creative industries mapping report. London: HMSO.Google Scholar

- Díaz de Chumaceiro, C. L. (1998). Serendipity in Freud's career: Before Paris. Creativity Research Journal, 11, 79–81.Google Scholar

- Díaz de Chumaceiro, C. L. (1999). Research on career paths: Serendipity and its analog. Creativity Research Journal, 12, 227–229.Google Scholar

- Díaz de Chumaceiro, C. L. (2004). Serendipity and pseudoserendipity in career paths of success ful women: Orchestra conductors. Creativity Research Journal, 16, 345–356.Google Scholar

- Diehl, M. & Stroebe, W. (1991). Productivity loss in idea-generating groups: Tracking down the blocking effect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 392–403.Google Scholar

- Drazin, R., Glynn, M. A., & Kazanjian, R. K. (1999). Multilevel theorizing about creativity in organizations: A sensemaking perspective. The Academy of Management Review, 24, 286–307.Google Scholar

- Dreistadt, R. (1969). The use of analogies and incubation in obtaining insight in creative problem solving. Journal of Psychology, 71, 159–175.Google Scholar

- Dunnette, M. D., Campbell, J., & Jaastad, K. (1963). The effect of group participation on brain-storming effectiveness for two industrial samples. Journal of Applied Psychology, 47, 30–37.Google Scholar

- Earl, W. L. (1987). Creativity and self-trust: A field study. Adolescence, 22, 419–432.Google Scholar

- Eisenberger, R. & Rhoades, L. (2001). Incremental effects of reward on creativity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81, 728–741.Google Scholar

- Eisenberger, R., Rhoades, L., & Cameron, J. (1999). Does pay for performance increase or decrease perceived self-determination and intrinsic motivation? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 1026–1040.Google Scholar

- Eissler, K. R. (1967). Psychopathology and creativity. American Imago—A Psychoanalytic Journal for the Arts and Sciences, 24, 35–81.Google Scholar

- Ellis, H. (1926). A study of British genius (rev. ed.). Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.Google Scholar

- Ericsson, K. A. (Ed.) (1996). The road to excellence: The acquisition of expert performance in the arts and sciences, sports, and games. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.Google Scholar

- Eulie, J. (1984). Creativity: Its implications for social studies. Social Studies, 75, 28–31.Google Scholar

- Eysenck, H. J. (1994). The measurement of creativity. In M. A. Boden (Ed.), Dimensions of crea tivity (pp. 199–242). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Google Scholar

- Feldman, D. H., Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Gardner, H. (1994). Changing the world: A framework for the study of creativity. New York: Praeger.Google Scholar

- Fischer-Kowalski, M. & Erb, K. (2003). Gesellschaftlicher Stoffwechsel im Raum. Auf der Suche nach einem sozialwissenschaftlichen Zugang zur biophysischen Realität [Societal metabo lism in space: In search of a social science approach to biophysical reality]. In G. Kohlhepp, A. Leidlmair, & F. Scholz (Series Eds.) & P. Meusburger & T. Schwan (Vol. Eds.), Erdkundliches Wissen: Vol. 135. Humanökologie: Ansätze zur Überwindung der Natur-Kultur-Dichotomie (pp. 257–285). Stuttgart, Germany: Steiner.Google Scholar

- Fischer-Kowalski, M. & Weisz, H. (1998). Society as a hybrid between material and symbolic realms: Towards a theoretical framework of society-nature interaction. Advances in Human Ecology, 8, 215–251.Google Scholar

- Florida, R. (2002). The rise of the creative class: And how it's transforming work, leisure, com munity and everyday life. New York: Basic Books.Google Scholar

- Florida, R. L. (2005). Cities and the creative class. New York: Routledge.Google Scholar

- Ford, C. M. (1996). A theory of individual creative action in multiple social domains. The Academy of Management Review, 21, 1112–1142.Google Scholar

- Forehand, G. A. & Gilmer, B. (1964). Environmental variation in studies of organizational behav ior. Psychological Bulletin, 62, 361–382.Google Scholar

- Forgays, D. G. & Forgays, D. K. (1992). Creativity enhancement through flotation isolation. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 12, 329–335.Google Scholar

- Frensch, P. A. & Funke, J. (1995). Definitions, traditions, and a general framework for understand ing complex problem solving. In P. A. Frensch & J. Funke (Eds.), Complex problem solving: The European perspective (pp. 3–25). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.Google Scholar

- Friedman, R. S. & Förster, J. (2002). The influence of approach and avoidance motor actions on creative cognition. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 38, 41–55.Google Scholar

- Funke, J. (2000). Psychologie der Kreativität (Psychology of creativity). In R. M. Holm-Hadulla (Ed.), Kreativität. Heidelberger Jahrbücher 44 (pp. 283–300). Heidelberg, Germany: Springer.Google Scholar

- Funke, J. (2007). The perception of space from a psychological perspective. In J. Wassmann & K. Stockhaus (Eds.), Experiencing new worlds (pp. 245–257). New York: Berghahn Books.Google Scholar

- Gagliardi, P. (1986). The creation and change of organizational cultures: A conceptual framework. Organization Studies, 7, 117–134.Google Scholar

- Gallo, D. (1989). Educating for empathy, reason and imagination. Journal of Creative Behavior, 23, 98–115.Google Scholar

- Galton, F. (1869). Hereditary genius: An inquiry into its laws and consequences. London: Macmillan.Google Scholar

- Gardner, H. (1988). Creative lives and creative works: A synthetic scientific approach. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), The nature of creativity (pp. 298–321). New York: Cambridge University Press.Google Scholar

- Gardner, H. (1993a). Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences. New York: Basic Books, London: HarperCollins.Google Scholar

- Gardner, H. (1993b). Creating minds: An anatomy of creativity as seen through the lives of Freud, Einstein, Picasso, Stravinsky, Eliot, Graham, and Gandhi. New York: Basic Books.Google Scholar

- Gardner, H. (1995). Creativity: New views from psychology and education. RSA Journal, 143, 5459, 33–42.Google Scholar

- Gibson, J. J. (1960). The concept of stimulus in psychology. American Psychologist, 15, 694–703.Google Scholar

- Gibson, J. J. (1979). An ecological approach to visual perception. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.Google Scholar

- Gieryn, T. F. (2000). A space for place in sociology. Annual Reviews of Sociology, 26, 463–496.Google Scholar

- Gieryn, T. F. (2002a). Give place a chance: Reply to Gans. City & Community, 1, 341–343.Google Scholar

- Gieryn, T. F. (2002b). What buildings do. Theory and Society, 31, 35–74.Google Scholar

- Gimbel, J. (1990). Science, technology, and reparations: Exploitation and plunder in postwar Germany. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.Google Scholar

- Givens, P. R. (1962). Identifying and encouraging creative processes: The characteristics of the creative individual and the environment that fosters them. Journal of Higher Education, 33, 295–301.Google Scholar

- Glynn, M. A. (1996). Innovative genius: A framework for relating individual and organizational intelligences to innovation. The Academy of Management Review, 21, 1081–1111.Google Scholar

- Goldsmith, R. E. & Matherley, T. A. (1988). Creativity and self-esteem: A multiple operationali-zation validity study. Journal of Psychology, 122, 47–56.Google Scholar

- Gordon, G. & Marquis, S. (1966). Freedom, visibility of consequences, and scientific innovation. The American Journal of Sociology, 72, 195–202.Google Scholar

- Götz, I. L. (1981). On defining creativity. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 39, 297–301.Google Scholar

- Gough, H. G. (1979). A creative personality scale for the Adjective Check List. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37, 1398–1405.Google Scholar

- Graumann, C.-F. (1996). Aneignung [Appropriation]. In L. Kruse, C.-F. Graumann, & E. Lantermann (Eds.), Ökologische Psychologie. Ein Handbuch in Schlüsselbegriffen (pp. 124–130). Weinheim, Germany: Psychologie Verlags Union.Google Scholar

- Graumann, C.-F. (2002). The phenomenological approach to people-environment studies. In R. B. Bechtel & A. Churchman (Eds.), Handbook of Environmental Psychology (pp. 95–113). New York: Wiley.Google Scholar

- Graumann, C.-F. & Kruse, L. (2003). Räumliche Umwelt. Die Perspektive der humanökolo-gisch orientierten Umweltpsychologie [Spatial environment: The perspective of environ mental psychology oriented to human ecology]. In G. Kohlhepp, A. Leidlmair, & F. Scholz (Series Eds.) & P. Meusburger & T. Schwan (Vol. Eds.), Erdkundliches Wissen: Vol. 135. Humanökologie: Ansätze zur Überwindung der Natur-Kultur-Dichotomie (pp. 239–256). Stuttgart, Germany: Steiner.Google Scholar

- Gray, C. E. (1958). An analysis of Graeco-Roman development: The epicyclical evolution of Graeco-Roman civilization. American Anthropologist, New Series, 60, 13–31.Google Scholar

- Gray, C. E. (1961). An epicyclical model for Western civilization. American Anthropologist, New Series, 63, 1014–1037.Google Scholar

- Gray, C. E. (1966). Measurement of Creativity in Western civilization. American Anthropologist, New Series, 68, 1384–1417.Google Scholar

- Guilford, J. P. (1967). The nature of human intelligence. New York: McGraw Hill.Google Scholar

- Hage, J. & Dewar, R. (1973). Elite values versus organizational structure in predicting innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 18, 279–290.Google Scholar

- Hanák, P. (1993). Social marginality and cultural creativity in Vienna and Budapest (1890–1914). In E. Brix & A. Janik (Eds.), Kreatives Milieu. Wien um 1900 (pp. 128–161). Vienna: Verlag für Geschichte und Politik.Google Scholar

- Hausman, C. R. (1979). Criteria of creativity. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 40, 237–249.Google Scholar

- Hellriegel, D. & Slocum, J. W. (1974). Organizational climate: Measures, research and contingen cies. The Academy of Management Journal, 17, 255–280.Google Scholar

- Hennessey, B. A. & Amabile, T. M. (1988). The conditions of creativity. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), The nature of creativity (pp. 11–38). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.Google Scholar

- Hennings, W. (2007). On the constitution of space and the construction of places: Java's magic axis. In J. Wassmann & K. Stockhaus (Eds.), Experiencing new worlds (pp. 125–145). New York/Oxford, England: Berghahn Books.Google Scholar

- Hocevar, D. (1980). Intelligence, divergent thinking, and creativity. Intelligence, 4, 25–40.Google Scholar

- Hoffman, L. R. (1959). Homogeneity of member personality and its effects on group problem-solving. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 58, 27–32.Google Scholar

- Hoffman, L. R. & Maier, N. R. F. (1961). Quality and acceptance of problem solutions by mem bers of homogeneous and heterogeneous groups. Journal of Abnormal und Social Psychology, 62, 401–407.Google Scholar

- Hoffman, L. R. & Smith, C. G. (1960). Some factors affecting the behavior of members of problem-solving groups. Sociometry, 23, 273–291.Google Scholar

- Holmes, F. L. (1986). Patterns of scientific creativity. Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 60, 19–35.Google Scholar

- Isaksen, S. G., Lauer, K. J., & Ekvall, G. (1999). Situational outlook questionnaire: A measure of the climate for creativity and change. Psychological Reports, 85, 665–674.Google Scholar

- Isaksen, S. G., Lauer, K. J., Ekvall, G., & Britz, A. (2000–2001). Perceptions of the best and worst climates for creativity: Preliminary validation evidence for the situational outlook question naire. Creativity Research Journal, 13, 171–184.Google Scholar

- Isen, A. M. (1987). Positive affect, cognitive processes, and social behavior. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 20, pp. 203–253). New York: Academic.Google Scholar

- Isen, A. M., Daubman, K. A., & Nowicki, G. P. (1987). Positive affect facilitates creative problem solving. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 1122–1131.Google Scholar

- James, L. R. & Jones, A. P. (1974). Organizational climate: A review of theory and research. Psychological Bulletin, 81, 1096–1112.Google Scholar

- James, L., Hater, J., Gent, M., & Bruni, J. (1978). Psychological climate: Implications from cognitive social learning theory and interactional psychology. Personnel Psychology, 31, 783–813.Google Scholar

- Jaušovec, N. (2000). Differences in cognitive processes between gifted, intelligent, creative, and average individuals while solving complex problems: An EEG study. Intelligence, 28, 213–237.Google Scholar

- Jeffcutt, P. (2005). The organizing of creativity in knowledge economies: Exploring strategic issues. In D. Rooney, G. Hearn, & A. Ninan (Eds.), Handbook on the knowledge economy (pp. 102–117). Cheltenham/Northampton/UK: Edward Elgar.Google Scholar

- Jöns, H. (2003). Grenzüberschreitende Mobilität und Kooperation in den Wissenschaften. Deutschlandaufenthalte US-amerikanischer Humboldt-Forschungspreisträger aus einer erweiterten Akteursnetzwerkperspektive [Cross-boundary mobility and cooperation in the sciences: U.S. Humboldt Research Award winners in Germany from an expanded actor-network perspective] (Heidelberger Geographische Arbeiten No. 116). Heidelberg, Germany: Selbstverlag des Geographischen Instituts.Google Scholar

- Jöns, H. (2006). Dynamic hybrids and the geographies of technoscience: Discussing conceptual resources beyond the human/non-human binary. Social & Cultural Geography, 7, 559–580.Google Scholar

- Kalliopuska, M. (1992). Creative way of living. Psychological Reports, 70, 11–14.Google Scholar

- Karau, S. J. & Williams, K. D. (1993). Social loafing: A meta-analytic review and theoretical integration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65, 681–706.Google Scholar

- Kasof, J. (1995). Explaining creativity: The attributional perspective. Creativity Research Journal, 8, 311–366.Google Scholar

- Kazanjian, R. K. (1988). Relation of dominant problems to stages of growth in technology-based new ventures. The Academy of Management Journal, 31, 257–279.Google Scholar

- Kerr, N. L. & Bruun, S. E. (1983). Dispensability of member effort and group motivation losses: Free-rider effects. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44, 78–94.Google Scholar

- Klausmeier, H. J. (1961). Learning and human abilities: Educational psychology. New York: Harper & Brothers.Google Scholar

- Kleinschmidt, H. (1978). American Imago on psychoanalysis, art, and creativity: 1964–1976. American Imago—A Psychoanalytic Journal for the Arts and Sciences, 35, 45–58.Google Scholar

- Klüter, H. (2003). Raum als Umgebung (Space as environment). In G. Kohlhepp, A. Leidlmair, & F. Scholz (Series Eds.) & P. Meusburger & T. Schwan (Vol. Eds.), Erdkundliches Wissen: Vol. 135. Humanökologie: Ansätze zur Überwindung der Natur-Kultur-Dichotomie (pp. 217– 238). Stuttgart, Germany: Steiner.Google Scholar

- Koch, A. (2003). Raumkonstruktionen [Space constructs]. In G. Kohlhepp, A. Leidlmair, & F. Scholz (Series Eds.) & P. Meusburger & T. Schwan (Vol. Eds.), Erdkundliches Wissen: Vol. 135. Humanökologie: Ansätze zur Überwindung der Natur-Kultur-Dichotomie (pp. 175–196). Stuttgart, Germany: Steiner.Google Scholar

- Koestler, A. (1964). The act of creation. London: Hutchinson.Google Scholar

- Kroeber, A. L. (1944). Configurations of culture growth. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.Google Scholar

- Kurtzberg, T. R. & Amabile, T. (2000–2001). From Guilford to creative synergy: Opening the black box of team-level creativity. Creativity Research Journal, 13, 285–294.Google Scholar

- Lamm, H. & Trommsdorff, G. (1973). Group versus individual performance on tasks requiring ideational proficiency (brainstorming): A review. European Journal of Social Psychology, 3, 361–387.Google Scholar

- Laughlin, H. P. (1970). The ego and its defenses. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.Google Scholar

- Leddy, T. (1994). A pragmatist theory of artistic creativity. Journal of Value Inquiry, 28, 169–180.Google Scholar

- Li, J. & Gardner, H. (1993). How domains constrain creativity. American Behavioral Scientist, 37, 94–101.Google Scholar

- Lindgren, H. C. & Lindgren, F. (1965). Creativity, brainstorming, and orneriness: A cross-cultural study. The Journal of Social Psychology, (ISSN-0022-4545) 67, 23–30.Google Scholar

- Lubart, T. I. (2000–2001). Models of the creative process: Past, present and future. Creativity Research Journal, 13, 295–308.Google Scholar

- Lubart, T. I. & Getz, I. (1997). Emotion, metaphor, and the creative process. Creativity Research Journal, 10, 285–301.Google Scholar

- Magyari-Beck, I. (1998). Is creativity a real phenomenon? Creativity Research Journal, 11, 83–88.Google Scholar

- Maitland, J. (1976). Creativity. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 34, 397–409.Google Scholar

- Mandler, G. (1992). Memory, arousal, and mood: A theoretical integration. In S. A. Christianson (Ed.), The handbook of emotion and memory: Research and theory (pp. 93–110). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.Google Scholar

- March, J. & Simon, H. (1958). Organizations. New York: Wiley.Google Scholar

- Martindale, C. (1989). Personality, situation, and creativity. In J. A. Glover, R. R. Ronning, & C. R. Reynolds (Eds.), Handbook of creativity (pp. 211–232). New York: Plenum Press.Google Scholar

- Martindale, C., Abrams, L., & Hines D. (1974). Creativity and resistance to cognitive dissonance. The Journal of Social Psychology, (ISSN-00224545) 92, 317–318.Google Scholar

- Matlin, M. W. & Zajonc, R. B. (1968). Social facilitation of word associations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 10, 455–460.Google Scholar

- Matthiesen, U. (2006). Raum und Wissen. Wissensmilieus und KnowledgeScapes als Inkubatoren für zukunftsfähige stadtregionale Entwicklungsdynamiken? [Space and Knowledge: Knowl edge milieus and knowledgescapes as incubators for sustainable urban development dyna mics]. In D. Tänzler, H. Knoblauch, & H. Soeffner (Eds.), Zur Kritik der Wissensgesellschaft (pp. 155–188). Konstanz, Germany: UVK Verlagsgesellschaft.Google Scholar

- Matthiesen, U. (2007). Wissensmilieus und KnowledgeScapes [Knowledge milieus and knowledgescapes]. In R. Schützeichel (Ed.), Handbuch Wissenssoziologie und Wissensforschung (pp. 679–693). Konstanz, Germany: UVK Verlagsgesellschaft.Google Scholar

- Mayer, R. E. (1999). Fifty years of creativity research. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Handbook of creativity (pp. 449–460). New York: Cambridge University Press.Google Scholar

- McCoy, J. M. & Evans, G. W. (2002). The potential role of the physical environment in fostering creativity. Creativity Research Journal, 14, 409–426.Google Scholar

- Meusburger, P. (1997). Spatial and social inequality in communist countries and in the first period of the transformation process to a market economy: The example of Hungary. Geographical Review of Japan, Series B, 70, 126–143.Google Scholar

- Meusburger, P. (1998). Bildungsgeographie. Wissen und Ausbildung in der räumlichen Dimension [Geography of education: Knowledge and education in the spatial dimension]. Heidelberg, Germany: Spektrum Akademischer Verlag.Google Scholar

- Meusburger, P. (2000). The spatial concentration of knowledge: Some theoretical considerations. Erdkunde, 54, 352–364.Google Scholar

- Meusburger, P. (2008). The nexus between knowledge and space. In P. Meusburger (Series Eds.) & P. Meusburger, M. Welker, & E. Wunder (Vol. Eds.), Knowledge and space: Vol. 1. Clashes of Knowledge. Orthodoxies and heterodoxies in science and religion (pp. 35–90). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer.Google Scholar

- Miller, A. I. (2000). Insights of genius: Imagery and creativity in science and art. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Google Scholar

- Mullen, B., Johnson, C., & Salas, E. (1991). Productivity loss in brainstorming groups: A meta-analytic integration. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 12, 3–23.Google Scholar

- Mumford, M. D. (1995). Situational influences on creative achievement: Attributions or interac tions? Creativity Research Journal, 8, 405–412.Google Scholar

- Mumford, M. D. (2003). Where have we been, where are we going? Taking stock in creativity research. Creativity Research Journal, 15, 107–120.Google Scholar

- Mumford, M. D. & Gustafson, S. B. (1988). Creativity syndrome: Integration, application, and innovation. Psychological Bulletin, 103, 27–43.Google Scholar

- Munro, T. (1962). What causes creative epochs in the arts? The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 21, 35–48.Google Scholar

- Neisser, U. (1987). From direct perception to conceptual structure. In U. Neisser (Ed.), Concepts and conceptual development: Ecological and intellectual factors in categorization (pp. 11–23). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.Google Scholar

- Nemeth, C. (1986). Differential contributions of majority and minority influences. Psychological Review, 93, 23–32.Google Scholar

- Neves-Graça, K. (2003). Investigating ecology: Cognitions in human-environmental relation ships. In G. Kohlhepp, A. Leidlmair, & F. Scholz (Series Eds.) & P. Meusburger & T. Schwan (Vol. Eds.), Erdkundliches Wissen: Vol. 135. Humanökologie: Ansätze zur Überwindung der Natur-Kultur-Dichotomie (pp. 309–326). Stuttgart, Germany: Steiner.Google Scholar

- Neves-Graça, K. (2007). Elementary methodological tools for a recursive approach to human-environmental relations. In J. Wassmann & K. Stockhaus (Eds.), Experiencing new worlds (pp. 146–164). New York: Berghahn Books.Google Scholar

- Niederland, W. G. (1967). Clinical aspects of creativity. American Imago, 24, 6–34.Google Scholar

- Norlander, T., Bergman, H., & Archer, T. (1998). Effects of flotation REST on creative problem solving and originality. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 18, 399–408.Google Scholar

- Ohnmacht, F. W. & McMorris, R. F. (1971). Creativity as a function of field independence and dogmatism. Journal of Psychology, 79, 165–168.Google Scholar

- Oldham, G. R. & Cummings, A. (1996). Employee creativity: Personal and contextual factors at work. The Academy of Management Journal, 39, 607–634.Google Scholar

- O'Reilly, C. A. (1991). Organizational behavior: Where we've been, where we are going. In M. R. Rosenzweig & L. W. Porter (Eds.), Annual review of psychology (Vol. 42, pp. 427–458). Palo Alto, CA: Annual Reviews.Google Scholar

- Osborn, A. F. (1953). Applied imagination. Principles and procedures of creative thinking. New York: Charles Scribner's.Google Scholar

- Ostwald, W. (1909). Grosse Männer [Great men]. Leipzig: Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft.Google Scholar

- Patrick, C. (1937). Creative thought in artists. Journal of Psychology, 4, 35–73.Google Scholar

- Patton, J. D. (2002). The role of problem pioneers in creative innovation. Creativity Research Journal, 14, 111–126.Google Scholar

- Paulus, P. B. (2000). Groups, teams, and creativity: The creative potential of idea-generating groups. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 49, 237–262.Google Scholar

- Paulus, P. B. & Dzindolet, M. T. (1993). Social influence processes in group brainstorming. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64, 575–586.Google Scholar

- Paulus, P. B. & Yang, H. (2000). Idea generation in groups: A basis for creativity in organizations. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 82, 76–87.Google Scholar

- Paulus, P. B., Larey, T. S., & Ortega, A. H. (1995). Performance and perception of brainstormers in an organizational setting. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 17, 249–265.Google Scholar

- Paulus, P. B., Larey, T. S., & Dzindolet, M. T. (2000). Creativity in groups and teams. In M. Turner (Ed.), Groups at work: Advances in theory and research (pp. 319–338). Hillsdale, NJ: Hampton.Google Scholar

- Peterson, M. F. (1998). Embedded organizational event: The units of process in organizational science. Organization Science, 9, 16–33.Google Scholar

- Plucker, J. A. & Renzulli, J. S. (1999). Psychometric approaches to the study of human creativity. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Handbook of creativity (pp. 35–61). New York: Cambridge University Press.Google Scholar

- Rappaport, R. (1979). Ecology, meaning and religion. Richmond, CA: North Atlantic Books.Google Scholar

- Raudsepp, E. (1958). The industrial climate for creativity: An opinion study of 105 experts. Management Review, 47, 4–8 and 70–75.Google Scholar

- Reber, A. S. (1992). The cognitive unconscious: An evolutionary perspective. Consciousness and Cognition, 1, 93–133.Google Scholar

- Redmond, M. R. & Mumford, M. D. (1993). Putting creativity to work: Effects of leader behav ior on subordinate creativity. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 55, 120–151.Google Scholar

- Rees, M. & Goldman, M. (1961). Some relationships between creativity and personality. Journal of General Psychology, 65, 145–161.Google Scholar

- Rescher, N. (1966). A new look at the problem of innate ideas. The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 17, 205–218.Google Scholar

- Robinson, J. (1970). Valéry's view of mental creativity. Yale French Studies, 44, 3–18.Google Scholar

- Rokeach, M. (1954). The nature and meaning of dogmatism. Psychological Review, 61, 194–204.Google Scholar

- Rokeach, M. (1960). The open and closed mind. New York: Basic Books.Google Scholar

- Runco, M. A. (1988). Creativity research: Originality, utility, and integration. Creativity Research Journal, 1, 1–7.Google Scholar

- Runco, M. A. (1993). Operant theories of insight, originality, and creativity. American Behavioral Scientist, 37, 54–67.Google Scholar

- Runco, M. A. (1994). Problem finding, problem solving, and creativity. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.Google Scholar

- Runco, M. A. & Okuda, S. M. (1988). Problem discovery, divergent thinking, and the creative process. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 17, 213–222.Google Scholar

- Russ, S. W. (1993). Affect and creativity: The role of affect and play in the creative process. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.Google Scholar

- Saaty, T. L. (1998). Reflections and projections on creativity in operations research and manage ment science: A pressing need for a shift in paradigm. Operations Research, 46, 9–16.Google Scholar

- Sadler, W. A. & Green, S. (1977). Feature Essay. Contemporary Sociology: A Journal of Reviews, 6, 156–159.Google Scholar

- Salbaum, J. (2008). Zeichen der Mehrdeutigkeit [Signs of polyvalence]. In H. Eigner, B. Ratter, & R. Dikau (Eds.), Umwelt als System—System als Umwelt? Systemtheorien auf dem Prüfstand (pp.155–169). Munich, Germany: Oekom.Google Scholar

- Schacter, D. L. (1992). Understanding implicit memory: A cognitive neuroscience approach. American Psychologist, 47, 559–569.Google Scholar

- Schein, E. (1985). Organizational culture and leadership. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.Google Scholar

- Schluchter, W (2005). Handlung, Ordnung und Kultur. Studien zu einem Forschungsprogramm im Anschluss an Max Weber [Action, order, and culture: Studies for a research program building on Max Weber]. Tübingen, Germany: Mohr Siebeck.Google Scholar

- Schorske, C. E. (1997). The new rigorism in the human sciences: 1940–1960. In T. Bender & C. E. Schorske (Eds.), American academic culture in transformation: Fifty years, four disciplines (pp. 309–329). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.Google Scholar

- Schuldberg, D. (2000–2001). Creativity and psychopathology: Categories, dimensions, and dynamics. Creativity Research Journal, 13, 105–110.Google Scholar

- Schumpeter, J. A. (1934). The theory of economic development: An inquiry into profits, capital, credit, interest, and the business cycle. Harvard Economic Studies, Vol. 46. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press (Original German work published 1912)Google Scholar

- Scott, S. G. & Bruce, R. A. (1994). Determinants of innovative behavior: A Path model of indi vidual innovation in the workplace. The Academy of Management Journal, 37, 580–607.Google Scholar

- Scott, W. E. (1965). The creative individual. The Academy of Management Journal, 8, 211–219.Google Scholar

- Shalley, C. E. (1995). Effects of coaction, expected evaluation, and goal setting on creativity and productivity. The Academy of Management Journal, 38, 483–503.Google Scholar

- Shalley, C. E. & Oldham, G. R. (1985). Effects of goal difficulty and expected evaluation on intrinsic motivation: A laboratory study. The Academy of Management Journal, 28, 628–640.Google Scholar

- Shalley, C. E. & Perry-Smith, J. E. (2001). Effects of social-psychological factors on creative performance: The role of informational and controlling expected evaluation and modeling experience. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 84, 1–22.Google Scholar

- Shalley, C. E., Gilson, L., & Blum, T. C. (2000). Matching creativity requirements and the work environment: Effects on satisfaction and intentions to leave. The Academy of Management Journal, 43, 215–223.Google Scholar

- Shaw, G. A. (1987). Creativity and Hypermnesia for words and pictures. Journal of General Psychology, 114, 167–178.Google Scholar

- Shekerjian, F. (1990). Uncommon genius: How great ideas are born. New York: Viking.Google Scholar

- Shore, E. (1971). Sensory deprivation, preconscious processes and scientific thinking. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 41, 574–580.Google Scholar

- Simonton, D. K. (1975). Sociocultural context of individual creativity: A transhistorical time-series analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 32, 1119–1133.Google Scholar

- Simonton, D. K. (1979). Multiple discovery and invention: Zeitgeist, genius, or chance? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37, 1603–1616.Google Scholar

- Simonton, D. K. (1981). Creativity in Western civilization: Intrinsic and extrinsic causes. American Anthropologist, New Series, 83, 628–630.Google Scholar

- Simonton, D. K. (1999). Creativity from a historiometric perspective. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Handbook of creativity (pp. 116–133). New York: Cambridge University Press.Google Scholar

- Simonton, D. K. (2000). Creativity: Cognitive, personal, developmental, and social aspects. American Psychologist, 55, 151–158.Google Scholar

- Slochower, H. (1967). Genius, psychopathology and creativity. American Imago, 24, 3–5.Google Scholar

- Smith, C. G. (1971). Scientific performance and the composition of research teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 16, 486–496.Google Scholar

- Stahl, M. J. & Koser, M. C. (1978). Weighted productivity in R & D: Some associated individual and organizational variables. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, EM-25, 20–24.Google Scholar

- Stamm, J. (1967). Creativity and sublimation. American Imago, 24, 82–97.Google Scholar

- Staw, B. M. (1990). An evolutionary approach to creativity and innovation. In M. A. West & J. L. Farr (Eds.), Innovation and creativity at work (pp. 287–308). Chichester, UK: Wiley.Google Scholar

- Staw, B. M., Sandelands, L. E., & Dutton, J. E. (1981). Threat-rigidity effects in organizational behavior: A multilevel analysis. Administrative Science Quarterly, 26, 501–524.Google Scholar

- Stein, M. (1953). Creativity and culture. Journal of Psychology, 36, 311–322.Google Scholar

- Sternberg, R. E. & Lubart, T. I. (1991). An investment theory of creativity and its development. Human Development, 34, 1–31.Google Scholar

- Sternberg, R. E. & Lubart T. I. (1999). The concept of creativity: Prospects and paradigms. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Handbook of creativity (pp. 3–15). New York: Cambridge University Press.Google Scholar

- Sternberg, R. E. & O'Hara, L. A. (1999). Creativity and intelligence. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Handbook of creativity (pp. 251–272). New York: Cambridge University Press.Google Scholar

- Suedfeld, P. (1968). The cognitive effects of sensory deprivation: The role of task complexity. Canadian Journal of Psychology, 22, 302–307.Google Scholar

- Suedfeld, P. (1974). Social isolation: A case for interdisciplinary research. Canadian Psychologist, 15, 1–15.Google Scholar

- Suedfeld, P. (1980). Restricted environmental stimulation: Research and clinical applications. New York: Wiley.Google Scholar

- Suedfeld, P. & Landon, P. B. (1970). Motivational arousal and task complexity: Support for a model of cognitive changes in sensory deprivation. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 83, 329–330.Google Scholar

- Suedfeld, P., Metcalfe, J., & Bluck, S. (1987). Enhancement of scientific creativity by flotation REST (restricted environmental stimulation technique). Journal of Environmental Psychology, 7, 219–231.Google Scholar

- Suojanen, W. & Brooke, S. (1971). The management of creativity. California Management Review, 14, 1, 17–23.Google Scholar

- Sutton, R. I. & Hargadon, A. (1996). Brainstorming groups in context: Effectiveness in a product design firm. Administrative Science Quarterly, 41, 685–718.Google Scholar

- Symington, N. (1987). The sources of creativity. American Imago, 44, 275–287.Google Scholar

- Tagiuri, R. (1968). The concept of organizational climate. In R. Tagiuri & G. H. Litwin (Eds.), Organizational climate: Explorations of a concept (pp. 11–32). Boston, MA: Harvard University Press.Google Scholar

- Thomas, C. A. (1955). Creativity in science: The eight annual Arthur Dehon Little memorial lecture. Cambridge, MA: MIT.Google Scholar

- Törnqvist, G. (2004). Creativity in time and space. Geografiska Annaler, 86 B, 227–243.Google Scholar

- Torrance, E. P. (1995). Why fly: A philosophy of creativity. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.Google Scholar

- Treffinger, D. J. (1995). Creative problem solving: Overview and educational implications. Educational Psychology Review, 7, 301–312.Google Scholar

- True, S. (1966). A study of the relation of general semantics and creativity. Journal of Experimental Education, 34, 34–40.Google Scholar

- Unsworth, K. (2001). Unpacking creativity. The Academy of Management Review, 26, 289–297.Google Scholar

- Van Gundy, A. (1987). Organizational creativity and innovation. In S. G. Isaksen (Ed.), Frontiers of creativity research (pp. 358–379). Buffalo, NY: Bearly.Google Scholar

- Vidal, F. (2003). Contextual biography and the evolving systems approach to creativity. Creativity Research Journal, 15, 73–82.Google Scholar

- Wallas, G. (1926). The art of thought. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company.Google Scholar

- Wassmann, J. (2003). Landscape and memory in Papua New Guinea. In H. Gebhardt & H. Kiesel (Eds.), Weltbilder (pp. 329–346). Heidelberger Jahrbücher No. 47. Berlin: Springer.Google Scholar

- Wassmann, J. & Keck, V. (2007). Introduction. In J. Wassmann & K. Stockhaus (Eds.), Experiencing new worlds (pp. 1–18). New York: Berghahn Books.Google Scholar

- Weichhart, P. (2003). Gesellschaftlicher Metabolismus und Action Settings. Die Verknüpfung von Sach- und Sozialstrukturen im alltagsweltlichen Handeln [Social metabolism and action settings: The link between technical and social structures in everyday action]. In G. Kohlhepp, A. Leidlmair, & F. Scholz (Series Eds.) & P. Meusburger & T. Schwan (Vol. Eds.), Erdkundliches Wissen: Vol. 135. Humanökologie: Ansätze zur Überwindung der Natur-Kultur-Dichotomie (pp. 15–44). Stuttgart, Germany: Steiner.Google Scholar

- Weisberg, R. W. (1999). Creativity and knowledge: A challenge to theories. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Handbook of creativity (pp. 226–250). New York: Cambridge University Press.Google Scholar

- West, M. A. (1989). Innovation amongst health care professionals. Social Behaviour, 4, 173–184.Google Scholar

- Westfall, R. S. (1983). Newton's development of the Principia. In R. Aris, T. Davis, & R. H. Stuewer (Eds.), Springs of scientific creativity. Essays on founders of modern science (pp. 21–43). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.Google Scholar

- Westland, G. (1969). The investigation of creativity. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 28, 127–131.Google Scholar

- Wierenga, B. & van Bruggen, G. H. (1998). The dependent variable in research into the effects of creative support systems: Quality and quantity of ideas. MIS Quarterly, 22, 81–87.Google Scholar

- Williams, W. M. & Yang, L. T. (1999). Organizational creativity. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Handbook of creativity (pp. 373–391). New York: Cambridge University Press.Google Scholar

- Witkin, H. A., Dyke, R. B., Faterson, H. F. Goodenough, D. R., & Karp, S. A. (1962). Psychological differentiation. New York: Wiley.Google Scholar

- Woodman, R. W. & King, D. C. (1978). Organizational climate: Science or folklore? The Academy of Management Review, 3, 816–826.Google Scholar

- Woodman, R. W. & Schoenfeldt, L. F. (1990). An interactionist model of creative behavior. Journal of Creative Behavior, 24, 279–290.Google Scholar

- Woodman, R. W., Sawyer, J. E., & Griffin, R. W. (1993). Toward a theory of organizational crea tivity. The Academy of Management Review, 18, 293–321.Google Scholar

- Workman, E. A. & Stillion, J. M. (1974). The relationship between creativity and ego develop ment. The Journal of Psychology, 88, 191–195.Google Scholar

- Zajonc, R. B. (1965). Social facilitation. Science, 149, 269–274.Google Scholar

- Zhou, J. & George, J. M. (2001). When job dissatisfaction leads to creativity: Encouraging the expression of voice. The Academy of Management Journal, 44, 682–696.Google Scholar

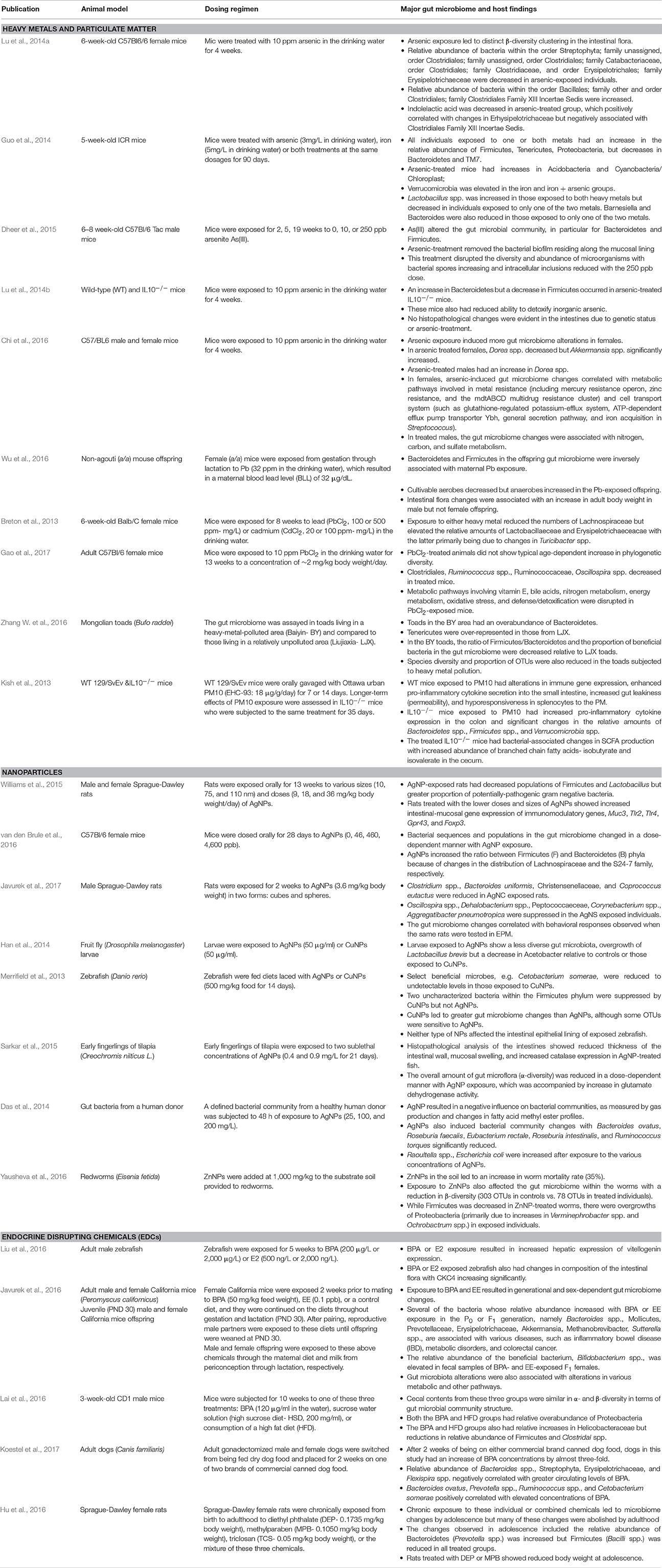

In Environmental Psychology (5th edition), on page 478, Table 14-1 shows the 'Relative Impact of Interventions to Save the Commons'. The authors weigh the impacts of 9 factors that influence 'environmentally sound behavior' and come up with the following table relating 'factor' to 'impact'. Psychology is the scientific study of the biological bases of behavior and mental states. Psychology is an academic and applied field involving the study of behavior, mind and thought and the subconscious neurological bases of behaviour. Psychology also refers to the application of such.